“Bird and Water”: Raja Baruah on the Hidden Zubeen Garg

On The Rita Chowdhury Podcast, percussionist Raja Baruah—among the earliest members of Zubeen Garg’s band—offers a doorway fans seldom get to enter.

What emerges is not a straight-line biography, but a lived portrait: first encounters and midnight rehearsals, tiny stages and long-haul flights, quiet kindness, creative restlessness, flashes of temper, and a personal philosophy that shaped one of Assam’s most cherished artists.

It’s a tribute built from small details: the thrill of a cassette deck’s sound, the warmth of a jacket gifted to a stranger, rain-soaked stages, and a belief that humans should live “like birds and water.”

The first meeting (Jorhat, 1989)

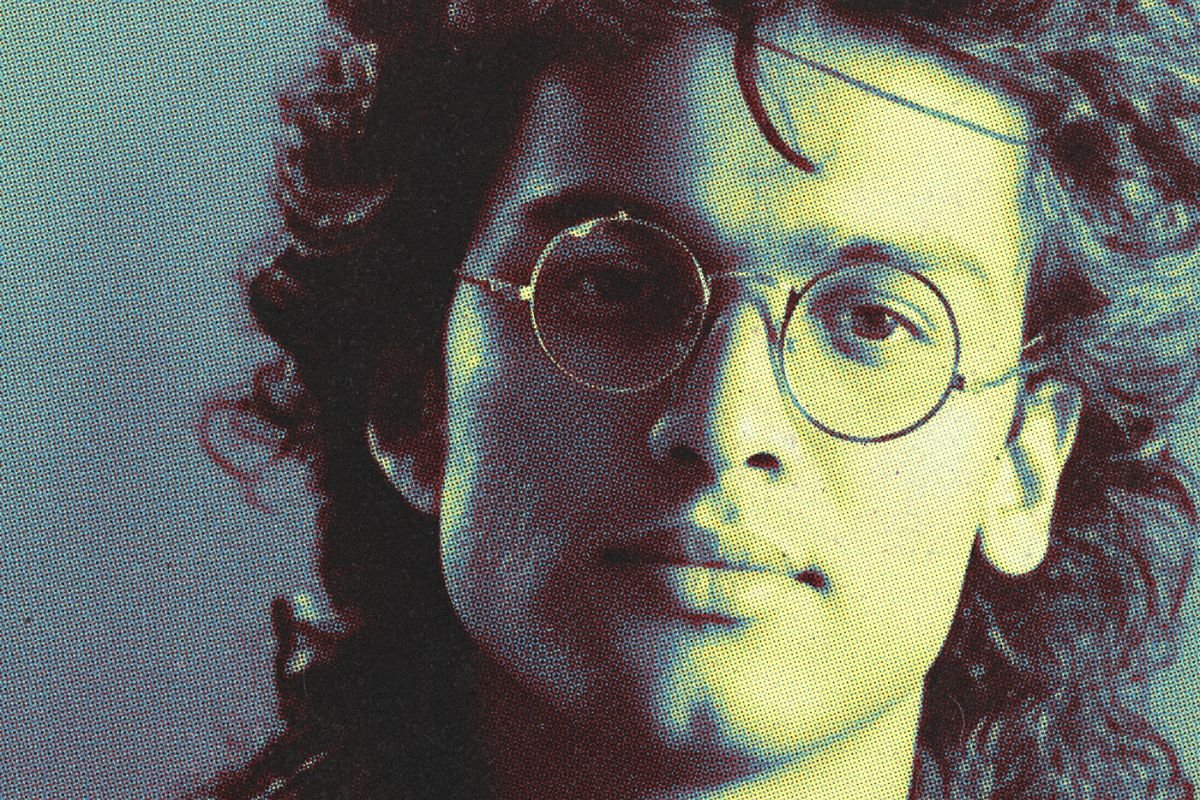

After his Class 10 exams in Jorhat, Raja met Zubeen at Bangalpukhuri Natya Mandir during a midday practice before a competition. A tall boy with wet curls and round glasses walked in, folded his hands, and said: “You play tabla really well.”

At lunch at Geetanjali Adhyapak’s home—Zubeen’s cousin—Raja felt an atmosphere shaped by books and conversation. Later, Zubeen played a Hariharan ghazal on a big deck, a moment that left Raja entranced by the tabla sound on “Keh De Mast Hai.” A cycle ride followed, with discussions ranging from Pather Panchali to film scoring. It was Raja’s first glimpse of Zubeen’s unusual curiosity.

A teenager with a vast library—of music and ideas

Zubeen’s room overflowed with cassettes: Pink Floyd, The Beatles (pronounced “Beseas” in Raja’s telling), Kenny Rogers, Kenny G, Bruce Springsteen—music he had already absorbed. He lectured on percussion and its roots in rhythm and time. He referenced Shivamani, Trilok Gurtu, Ritwik Ghatak, Ajantrik, Vivekananda, and the Gita, shifting between Assamese, Bengali, and English. When Raja avoided an omelette on a Tuesday for superstition, Zubeen gently insisted: “Days came later; humans came first.” It was the young artist’s logic urging first principles.

Composer before “star”: the Jorhat years

Before fame found him, composition was already his native language. In Class 8, he wrote “Gane Ki Ane” and “Eti Nohoy Duti Nohoy,” sung by his sisters Jonki and Geetanjali. He claimed instruments mattered more to him than singing. His first major stage plan collapsed when heavy rain brought down the pandal. Another story added to the pile.

He secured a keyboard from Bhupen Uzir’s studio, supported by cousin Utpal Sharma. Rehearsals at Leena Bezbaruah’s home became a ritual. When he sang—even a half-remembered tune—the room paused. Admiration didn’t inflate his ego; it sharpened his curiosity.

Anamika: the cassette that changed everything

Recording was expensive. N.K. Production would market the album, but the costs were real. His mother took a ₹60–70,000 cooperative bank loan to fund Anamika. Its success changed his trajectory, but Raja insists the man remained the same: thoughtful, stubborn, curious, playful, generous.

Style, thrift, and Shillong’s second-hand market

Despite his father’s official post, Zubeen loved street thrift—“longshi” clothes arriving from distant ports through Shillong onto Jorhat’s footpaths. He had an instinct for style: if Raja picked corduroy, Zubeen chose pinstripes, and everything looked right on him. The flair came long before the fame.

The Chennai detour: empty pockets, full hearts (1991)

A month-long trip to Madras with the Assam Association left them broke after rehearsals and a successful show. With about ₹800 between them and weeks to wait for tickets, they slept on mattresses with students, watched Roja at Ashok Pillar, and returned to Jorhat on a ₹100 note Zubeen had saved for bus fare. For him, money was a tool to create music, not a measure of worth.

Radical generosity: houses, instruments, and midnight dinners

The stories pile up.

He gave Raja the government housing board flat he’d been allotted, later helping transfer it in Raja’s name.

He gifted instruments—a rare African Udu drum to a promising young player, a ₹1.5-lakh keyboard to someone who needed one.

After shows, he fed the entire crew at a dhaba, waited until everyone ate, then packed his own meal to eat later.

Visitors to his home at 10:30 a.m. never left without lunch.

He was famously unconcerned about money; people handed him bundles claiming to be ₹1 lakh that turned out to be ₹10,000, and he simply shrugged. On stage once, he joked about building a house for three years—never a complaint, just a reflection of a life where money was incidental.

Courage on the road: jackets, wheelchairs, rescues

His empathy was active, decisive.

On a winter night at Baruah Chariali, he placed his white jacket around a shivering man near a tea stall and cycled home bare-armed.

He bought a wheelchair for a begging man who had no legs.

He cleared a traffic jam by calling the police when a misparked fire engine blocked the road.

He rescued accident victims at Numaligarh before a show, driving them to the hospital.

He climbed onto a truck to help an injured driver, fearless and focused.

These acts weren’t for cameras. They were instinct.

Creative restlessness: the river, not the pond

When people complained his “new songs weren’t like the old,” he replied: “Music isn’t a pond; it’s a river.” He altered rhythms, arrangements, and the emotional texture of language. He introduced lines like “Tumar ei abogunthan” and opened a song with “Endhaar hobo nuaru”—a bold beginning with “darkness.”

At his most detailed, he arranged everything himself. As he delegated more, listeners may have sensed the shift.

He poured himself into every language he sang—Assamese, Bodo, Rabha, Bengali—becoming the “missing boy” each culture recognized.

The philosopher under the pop icon

On long flights, he read autobiographies and philosophy—Chaplin, Napoleon, Alexander—and hunted for a Michael Jackson biography until he finally found one at Bishal Kalita’s home. He spoke of nihilism, existentialism, and questioned rituals shaped by humans. At Kamakhya he once asked to stop buffalo sacrifice—not to provoke, Raja says, but from conviction. He could joke about custom and then quote the Gita with tenderness.

He often said: “I see things more clearly from a distance.” Raja maintained that distance for 35 years—close enough to play, far enough to truly perceive him.

Anger, emotion, and the private man

His anger was childlike and principled—triggered when things didn’t go as planned or someone crossed a boundary. As a teenager slighted by a classmate, he declared: “One day you’ll run after my car and eat dust.” A few years later, he was indeed a star.

His tears were for others. At Patacharkuchi, hearing that a young woman he had been supporting through cancer had passed away, he cried on stage and cancelled the show. At Balipara, memories of Jonki’s accident overwhelmed him mid-performance. He cried at Naba’s cremation though the man had been in the team just two years.

For himself, he hid emotion behind humour and talk of 28-inch waists and stamina.

Family, loss, and Garima’s quiet center

He adored his mother, teasing her often. During her illness, Raja helped with hospital visits; the late diagnosis of liver cirrhosis weighed heavily on him. Jonki’s death—after trading cars with him—haunted him, though he told friends he had moved on by choosing to keep working.

In that fragile time, Garima became anchor: cooking, grinding herbs, handling medicines, feeding him when he resisted food, and preparing for long stays at Rudra Singha Resort to be close to nature. Raja calls it mothering—care without diminishing.

Nature as a collaborator

Zubeen planted endlessly. His homes in Kharghuli and Junali were green sanctuaries, even producing blueberries. He sang in the rain, stepped off stage into showers, and joked that he could “shake the trees.” He believed nature and humans were partners, not opponents. He hated unnecessary tree cutting and felt everything thrives with attention.

“I am there”: management, overload, and the machine

Success filled his calendar—shows, films, dubbing in five studios, nonstop recordings. He would sometimes snap: “I’m not a machine, man.” Raja thinks management sometimes shielded Garima from the true workload. Yet his constant reassurance to friends remained: “I am there—don’t worry.”

He said it about cars, money, medical help, courage—whatever someone needed.

The museum day and the last plans

On 16 September, he arrived early at Bishal Kalita’s home to inaugurate a Zubeen Garg song museum. He joked that the paper-bomb felt like a birthday gift and finally saw the true count of his songs—including two Tamil tracks painstakingly located.

He spoke about “nothingness,” flew on the 17th, planned to return on the 22nd to work on background music. Raja had ordered new instruments for him to explore. The future felt full, as always.

The image Raja would paint

Asked how he’d paint Zubeen, Raja said he wouldn’t paint the body—he’d paint a soul and call it “Great Soul.” The man he followed across stages and highways, through studios and storms, had become abstract: water taking the shape of its container, a bird landing wherever it wished.

Legacy: a science beyond measure

Driving from Jorhat, Raja reached Sonapur at 4:25 a.m. and saw two thousand people singing. He calls it a science—mechanical or spiritual, he cannot say. He only knows his own knowledge feels small beside Zubeen’s curiosity, courage, and compassion.

A jacket on a stranger. A wheelchair for a beggar. A house given to a friend. A song perfected until it held soul. The courage to challenge rituals and embrace rain. The belief that music must move like a river.

What remains is not a man defined by dates and discographies but a principle—to help, to learn, to risk, to evolve, to love intensely, and to work until the work is done.

And in the quiet after the music, you can still hear him say:

“I am there. Don’t worry.”